by Brad Houle, CFA

Executive Vice President

by Brad Houle, CFA

Executive Vice President

Inflation is an obtuse concept to fully comprehend. For the month of September, the Bureau of Labor Statistics indicated that the rate of inflation, as measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI), was 1.7 percent for the last year. This would hardly be considered a noticeable price increase for most items. As a consumer, it seems that everything other than flat screen televisions is more expensive all the time, particularly if you consume prescription drugs, go to the doctor or pay for any type of tuition.

It is a fairly consistent complaint among the investment community that the CPI understates the rate of inflation. In fact, there are often conspiracy theories around the measure of inflation because the CPI is the basis for cost-of-living increases for Social Security recipients and other government payments to individuals which is consuming an ever greater percentage of the national income.

In looking at the detail of how the CPI is calculated, it is apparent that a great deal of thought went into the methodology while its value in measuring the true rate of inflation is questionable. As for the conspiracy theories around the inflation measure, it is unlikely that a giant bureaucracy is organized enough to pull off anything like that. No doubt well-meaning people work hard to produce these statics.

Too much or too little inflation is a bad thing. Excess inflation, such as was experienced in the late 1970s in the United States, or hyper-inflation that often occurs in developing nations can create an environment where costs spiral out of control. Conversely, negative inflation or deflation is also a troublesome scenario. In deflation, prices continually drop and as a result, consumption also goes down as consumers wait for lower prices. Japan has suffered from this condition to some degree for the last decade and is attempting to climb out deflation via aggressive economic stimulus.

Following aggressive monetary policy action taken by the Federal Reserve following the financial crisis, there was great concern that excess inflation would follow. Thus far, there has been no excess inflation despite the flood of liquidity put into the financial system to stimulate the economy. In fact, inflation is below where the Fed would like to see it. The Fed's preferred measure of inflation called the PCE Deflator which last month has a yearly increase of 1.5 percent and generally is lower than the CPI. The primary difference between the two measures of inflation is the PCE Deflator allows for the substitution of goods by consumers. The Fed would like to see the PCE Deflator closer to 2 percent.

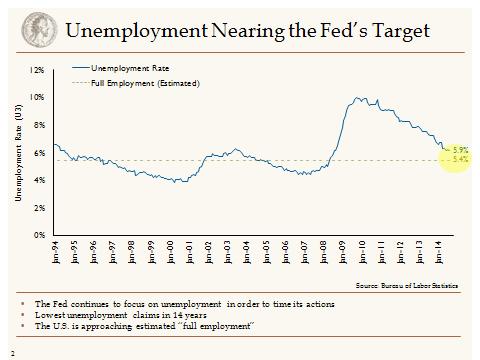

The attempt to control and measure inflation produces more questions than answers. Inflation is very difficult to quantify and measure. There is no such thing as an average consumer and people are going to experience inflation very differently depending upon their stage in life and level of income. We believe that inflation is muted due to the long, slow recovery we’ve experienced since the financial crisis. The slack in the labor market and broader economy is just now beginning to get wrung out.

The attempt to control and measure inflation produces more questions than answers. Inflation is very difficult to quantify and measure. There is no such thing as an average consumer and people are going to experience inflation very differently depending upon their stage in life and level of income. We believe that inflation is muted due to the long, slow recovery we’ve experienced since the financial crisis. The slack in the labor market and broader economy is just now beginning to get wrung out.

Our Takeaways for the Week

The equity markets were strong this week, up around 3 percent as we move through third quarter earnings season. According to data compiled by Bloomberg, about 79 percent of S&P 500 companies that have posted quarterly earnings this season have topped analysts’ estimates for profit, while 60 percent beat sales projections. In addition, the hysteria around Ebola now being called “Fearbola” has hopefully subsided.